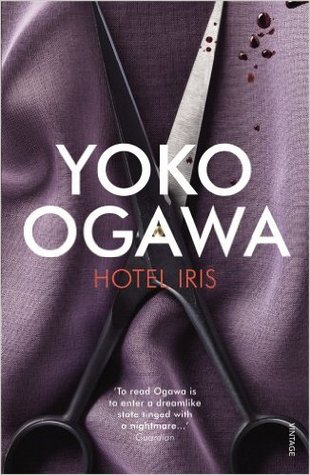

Of Ogawa’s vast scope of work, I had read The Housekeeper and The Professor, which remains one of my favourite books; I read Ogawa’s interview with the famed mathematician, Masahiro Fujiwara, whom she met as part of her research for her novel; I read The Memory Police, which was as equally delicate as the first title, and on the same topic of losing our most defining possession – our memory. I was left quite surprised when I read Hotel Iris, which is about a quiet 17 year-old woman who starts a sadomasochistic relationship with a much older gentlemen.

What I love about the previous two novels I mentioned was the lack of sex. Graphic description of intercourse has become very prevalent in modern writing, and even more so in Japanese literature (Murakami- who I do read, comes to mind). There is a clear progression of sex in literature, and no doubt it is a correlation to our own cultural understanding of it. Remember Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, in which we only guess at the love affair carried out in the back of a carriage? For women to write about sex, too, was and still is a huge form of liberation. Yet, at the risk of sounding a prude, I keep wondering, at what point does a graphic description of sex in literature lose its purpose and cross over to pornographic? My own conclusion – sex becomes fluff when it doesn’t drive the plot. For an honest account of the act there is Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous. There is meaning to his words; it wasn’t about sex – it was about vulnerability.

To be fair to Ogawa, she was frugal in her sex prose, despite the plot in Hotel Iris. The novel is a closer look at the relationship between the unlikely pair who are both quiet, gentle, and socially ‘odd’. The pair meet at the hotel in which he was a guest, after a loud altercation between him and the prostitute he hired for the night. Mari works at the tawdry hotel, where her abusive and controlling mother is the hotel’s proprietress. The teenager is without a father; he is a Russian translator who lost his young wife in a tragic accident. Both have a need for love to be expressed violently, a pain that needs to be rectified without tenderness. Even aside the couple, the surrounding characters, too, swing from polite to abusive tempers and for a lack of better word, there is an experience of whiplash between the two personas – the one we hide, the one we show. For the couple, S&M functions as a ferry between the two.

The reader will be well advised not to mistake this for 50 Shades. As the sadistic powerplay progresses, there is a terrible sense of fear for the young woman’s life. But the storm passes (literal, metaphysical) and Mari is saved – from both ill repute and the violent relationship. Then: a small small hint at the very end makes the reader wonder who the real masochist was. The subtle twist is very much the author’s forte, and despite my personal aversion to the story, there is no mistaking Ogawa’s quietly distinctive style and mind at work.

At its core, S&M play is extremely vulnerable. There are many expressions of love, and not every one of them is what we easily define as beautiful.

I became other things as well. A table, a shoe cupboard, a clock, a sink, a garbage can. He used the cord to twist my body into these shapes, tying my arms and legs, my hips, my chest, my neck. He worked quickly, binding wrists to drawer pulls, hips to doors, fingers to knobs. The cord obeyed him, and he used it to bend and tie me into whatever shape was in his head.

Leave a comment