Growing up I loved reading myths. Greeks were my favourite – still are. Wanting to revisit the Japanese myths of my youth, of fantastical creatures and cursed spirits, I recently read the Pantheon Collection of Japanese Tales. Imagine my surprise when I encountered sexually depraved monks taking advantage of sleeping princesses, potty-mothed samurais, and a Goddess who saved the ‘offerings’ of her mortal lover, in a story titled Seven Pails of Bliss. Yes, seven pails.

My mistake was in category. I definitely mixed up the PG/R ratings. But it goes a step beyond. The stories of my childhood were of local lore, deities whose power is often tied to the surrounding nature. Collated, these stories fall under the Shinto religion. The Pantheon Collection were stories passed on by early Japanese Buddhist monks. Many of the stories had travelled from India to China before crossing the sea, resulting in many strange interpretations of the doctrine.

I do believe there was a time when the stories needed to be separated under different beliefs for the purpose of teaching. The Bible is a collection of stories, edited under council, to form the narrative of Jesus. Under the same logic of classification, it is commonly put that Japan follows two religions – Shintoism and Buddhism. But I believe that to be outdated. In today’s Japan, when a person asks, ‘what religion do you follow,’ they are really asking ‘who reads the prayers at your funeral, a monk or a priest?’ The ethical, moral and spiritual guidance during a person’s life comes from culture – a mix of, old wives’ tales, half-truths, stories to keep children in line, borrowed language, borrowed philosophies: Zen, Stoicism, Confucianism, Nihilism, Minimalism …– all brewed together in a cauldron to form a distinctive narrative and code of conduct. Culture.

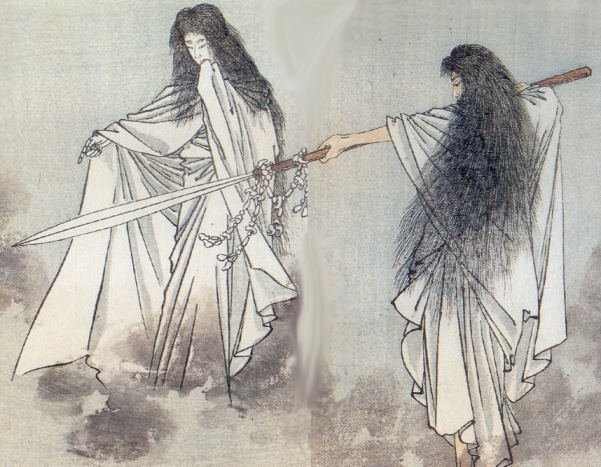

The reason why I felt the need for this long preamble, was to say that I believe The Goddess Chronicle to be a new generation of myth – a mix! It is a weaving of so many global legends, religious thoughts and narratives. Even the origin story of Japanese primordial Gods mirrors the myths of Greek Titans. The idea of heavenly pairs is also a very familiar global theme. The Chinese ancient philosophy of Ying and Yang (another expression of pairs), even drives the plot of this retelling. Death as ‘defilement’, is a very old Buddhist thought. Add to it the very infamous narrative, ‘Hell hath no fury like a ….’

The Goddess Chronicle retells the myth of god Izanagi and sister-wife Izanami, birth parents to the islands of Japan. One day the goddess dies in childbirth and becomes bound to the Underworld. How does the immortal die? Because she is a woman, Kirino answers; simple and adequate with just the right amount of venom. For birth has a price, and that is death – of body, of youth, of beauty, of independence. The axe falls heavy on a woman’s shoulders. And oh, how we scorn when we find out of this injustice. Can we be blamed to have such hell-fury?

In Japanese, ‘culture’ (文化) literally translates ‘to change the written word’. Culture is a state in flux. It should not be confused with the unyielding twin: ‘tradition.’ Kirino’s reinterpretation is relevant because it redefines boundaries of cultural stories, and consequently, of women and their stories too. In the past we thought it pertinent to categorize – country, religion, culture, gender roles, political ideology. Such arbitrary boarders have forced a perspective: them or us. What is important now is to cultivate the stories of what we share, with the purpose to reconnect to our humanity. Is that not all cultures’ true aim? As Kirino writes, mutual association of these opposite ends – common and unique – “enrich(es) the meaning of both.”

‘Then Izanami-sama, why do you suffer? I asked without thinking.

‘Because I am a female god.’

…what a complete illusion the human body is. All that remains is the heart.

Heaven and earth, man and woman, birth and death, day and night, light and dark, yang and Ying. You may wonder why everything was paired in this way, but a single entity would have been insufficient. In the beginning, two became one, and from that union came life. Whenever a single entity was paired with its opposite, the value of both became clear from the contrast – and the mutual association enriched the meaning of both.

Leave a comment