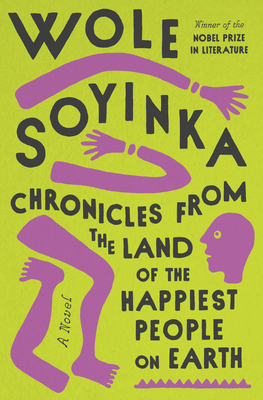

This was by far one of the most difficult reads of recent years, the last one being Moby Dick and prior to that, The Sea of Fertility tetralogy by Mishima. The experience is worth the initial struggle; readers – onwards!

The tone is sartorial, scathing, dark. Macabre, with the tenderest of moments. Wordplay prevails. There is a polarization between the chronicles which follow four characters, and the story’s backdrop which is so utterly dysfunctional in its degree of chaos. Things are said by not saying, spoken in code, or insinuated – communication methods of the mob, or those living in a system of corrupt opportunism (same same). Only while lying in at night comes the realization of the horrible things that flowed in the background like music. As the stories progress, the four ambitious characters who once stood above the corruption, are proven to be either part of the problem, or helpless against it.

The land of the happiest people on earth is an amalgamation of social constructs, religions, and myths, without a unifying narrative and where corruption prevails. The country resorts to manufacturing happiness through the nationwide competition for the best person award (criteria for entry is video evidence of an altruistic deed); and through a mixed religion that pairs mysticism with the abracadabra clean slate of Christian forgiveness. Justification of actions comes from ANY of the many myths, resulting in societal tolerance of rampant violence. Only a congested highway serves as the literal fabric of unification, leading its people back and forth between two cities.

On this freeway is where an altercation with a driver and vendor becomes gladiatorial. People clamour over cars to witness and participate in what becomes a public execution by stoning. A machete is pulled out as people que for the bus. A head rolls. In the city, suicide bombings are a regular occurrence. Aside from Boko Haram there are lawyers and their sons raping prepubescent children, either due to the tempting devil or for some other reason. It doesn’t matter what – the result is the same. Someone dying on the operating table.

All this happens in the background, until it doesn’t. We mostly experience the horrors through the professional detachment of the surgeon, Dr Bedside Manners, aka Gumchi Boy. Whatever the narrative in which the violence is delivered, the doctor witnesses its effects daily. Now at the height of his career, he is left with a broken soul and “rage – murderous rage.” Leaving behind his now recognized career (he too, was bestowed an award for restoring a nation, one broken body at a time) he turns to his childhood friends who in their youthful naiveté, promised to modernize Gumchi- his humble place of origin.

What makes the book difficult is the unfamiliar reality – or so I thought. I would remember the name of the gang responsible for kidnapping 300 girls from a school, condemned ubiquitously THEN on news channels. ‘Surely this mystic and sacrificial violence no longer prevails,’ I think. Wishes and ignorance. Soyinka only has to mention, zoom calls, hand sanitizers, and ‘I cannot breathe’, to place this story NOW.

It is easy to look away when we believe ourselves far more progressive than to engage in ‘tribal disputes.’ We don’t recognize it as the same myth when we call it ‘patriotism,’ or even ‘democracy.’ We are all dupes of manufactured loyalty, limited by our ancestral genetics of territorial animals. As to happiness? The state needn’t provide; we in the west have free markets for that.

Violence continues, Soyinka reminds.

Yes. Yes it does.

Through the weary, surgical eyes of Dr Menka, I met Wole Soyinka. And now my heart is in Gumchi. A small village where the kola nut grows. A place I never knew existed. To him I plead: Writer, heal thyself.

…martyrdom was no longer content with willing submission to persecution and death or even self-immolation in a cause, but required the immolation of nonconsenting adults and children, anywhere, anytime, in motor parks, marketplaces, schools, and allied institutions, in leisure places and workplaces.

It challenges the collective notion of soul. Something is broken. Beyond race. Outside colour or history. Something has cracked. Can’t be put back together.’

Leave a comment