BBC Article: Five must-read books from Japanese literature

By Johanna Airth 18th December 2019

With the translation of Japanese literature into English, new meaning is given to the texts which illuminates our understanding of Japanese culture

Understanding Japanese culture has fascinated the Western world ever since the country’s trading doors opened up in the 1800s. Eating raw fish was an idea once met with a certain grimace, yet sushi is now enjoyed globally. Once again there are kimono-clad maidens riding rickshaws in the streets of Kyoto, only now it is part of a tourist attraction. There is no denying that Japan has remained elusive, and people have travelled from all corners of the world to see for themselves just how unique this island remains. Another way of looking inside this enigmatic culture, from the everyday to the sensationalised, is through its literature.

Broadly speaking, Japanese authors tend to write of their underlying acceptance of life. It is a stark contrast to the Western culture’s emphasis on ‘hope’ or expectations for a better future. Instead, the Japanese emphasis is on the present. At first glance, Japanese literature can seem grim or passively nihilistic. But looking deeper we see the beauty of a fleeting moment. This simple zen-like logic on the transient nature of all things permeates all generations and facets of Japanese culture.

More from Japan 2020:

Why all film lovers should watch anime

Japan’s love of goldfish in art

Japan’s ‘retro economy’

Although Japanese culture can be conceptualised as refined minimalism, the language, on the other hand, is complexity itself. Written Japanese has not one but three sets of characters. Kanji, derived from Chinese, and what are known as the Japanese alphabets – hiragana and katakana.

Added to that, formal versus informal tones of the language make the narrative voice either too austere or too casual. Translating texts from Japanese to English surprisingly does away with all such difficulties. And while the essence of novels in Japanese can be quite hard to grasp sometimes, English fills the gaps that were lost in cultural subtlety (and let’s face it, kanji). Even in translation there is a flow of words that is unique to the Japanese writer. It seems strange that English would unlock the mystery of the Japanese sentiment, yet this enigma is precisely so Japanese. The recommended books are all available in English – many translated by Japan enthusiasts, guiding our understanding with added definitions and helpful footnotes.

Story continues below

(Credit: Penguin Classics)

The Penguin Collection of Japanese Short Stories

(Penguin Classics, 2018)

The Penguin Book of Japanese Short Stories is an eclectic collection by various authors such as Haruki Murakami, Yasunari Kawabata, Banana Yoshimoto. In a whimsical forward, Murakami explains how the collection is to serve as an introduction to Japanese literature. Despite the span of time and space, there is an underlining cohesiveness in that the authors are undeniably Japanese; their eye level is low and microscopic, like that of a haiku poet, somehow managing to grasp universal truths. That ‘universal truth’ often has Zen undertones, intertwined with Shinto fables of spirits and legends. While the short stories are mostly listed historically – starting in the Meiji Restoration period, through World War Two, followed by the tsunami of 2011 – the book is organised thematically, with titles such as Nature and Memory, Men and Women and Dread.

The authors rarely focus on the ‘why’, nor are they in awe of destructive powers. Instead Akiyuki Nosaka, for example, writes of a post-war sentiment, expressed crassly and simply as a man who feels defeated in sexual mastery against an old American soldier in the short story American Hijiki. While Kazumi Saeki sees something worth fighting for, while standing atop a hill, looking over the buildings that were washed away in the tsunami in Weather-Watching Hill.

And when this feeling strikes me, I find myself in tears, for in truth there is then no self, no other. I am touched by thought of each and every one – Unforgettable People, Doppo Kunikida

(Credit: Vintage)

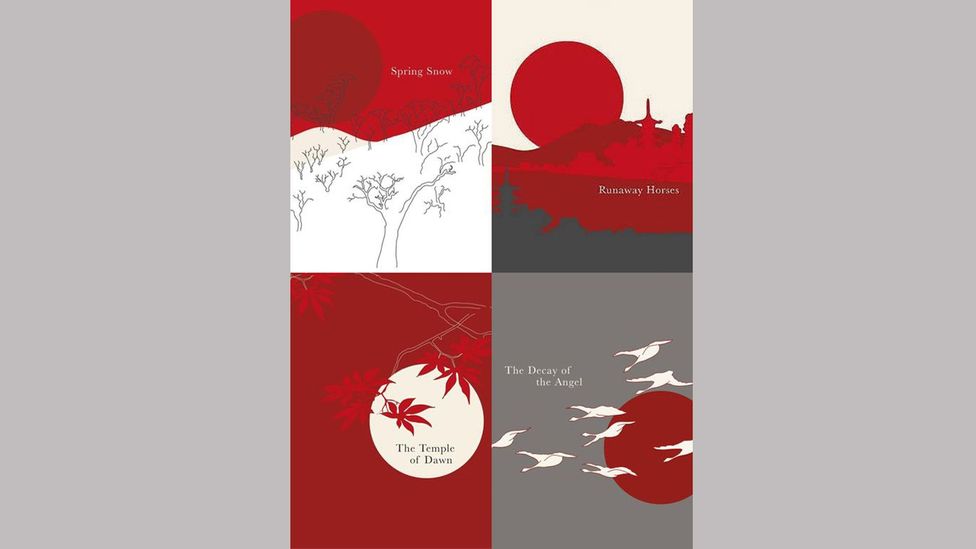

The Sea of Fertility series by Yukio Mishima

(Vintage, 1999)

Mishima is known as an eccentric, but there is no doubt of his genius. Born in 1925, he fuses traditional Japanese sentiment with Western-style writing. He is most famous for The Temple of the Golden Pavilion (1959), in which the obsessive protagonist sets fire to the subject of his insanity; the Golden Pavilion in Kyoto now one of the most tourist-clogged cities. Mishima’s detailed analyses of the dark and twisted subject matter of his writing is reminiscent of Dostoevsky. However, his last penned tetralogy The Sea of Fertility, details the metamorphosis that Japan underwent during the early 1900s, making it as significant in Japanese history as Tolstoy’s War and Peace.

The tetralogy, comprised of the novels Spring Snow, Runaway Horses, The Temple of Dawn, and The Decay of the Angel, delicately balances the rational and absurd. The four novels span from 1912 (just after the Russo-Japanese war) to post-war Japan in 1975. Western ideas and their influence on Japan’s economy and culture, serve as backdrops and motives for various characters throughout the story. The first novel is the story of star-crossed lovers while the second book moves to themes of reincarnation and Buddhist philosophies. By the third book, the protagonist suffers a sudden moral fall; steadfast in his belief that he is to be an observer of life, he becomes a literal one – a perverted voyeur looking through various peepholes. But the reader still clings to a sliver of hope, that perhaps the protagonist, who has fallen so low in our esteem, will be redeemed in the fourth and final book. Mishima’s genius delivers yet in the most unexpected way.

It is perhaps the greatest upset in the history of literature, which alone is worth trudging through the tangle of Buddhist philosophy. Not one to be outdone by his art, Mishima took his own life the day after he handed in his final copy of the final book, having staged a failed military coup.

(Credit: Tuttle Publishing)

Modern Japanese Short Stories

(Tuttle Publishing, 2019)

Here is another excellent and thorough collection of 25 short stories. In the forward, the book’s editor, Ivan Morris, who translated some of the stories, provides a brief Japanese history from the Meiji Era, when the Western form of literature was first introduced to Japan. Foreign novels were often translated by the Japanese authors, who then in turn were heavily influenced by the literary movement of the time. He writes, “The introduction into Japan of the writings of Zola and Maupassant had far-reaching effects in literary circles. It accelerated the movement away from the traditionalism and, at about the time of the Russo-Japanese War (1904-05), produced a group of influential writers who proclaimed that the purpose of literature was to search for the truth and to describe it with the detached accuracy of a scientist.”

Some stories are quite simple in plot, provoking the reader to stop and reflect. The Camellia by Ton Satomi, is once such tale: two sisters lie close in bed in their new home. One wakes up in hysteria when a camellia flower drops loudly on the floor – an ominous sign. Then they slowly start laughing, and build up to a frenzy, only moments afterwards. We are left wondering what is the secret they laugh at?

But other stories are great windows into the social scenery. Machine by Riichi Yokomitsu is a criticism of the gruelling working conditions at the time, written from the point of view of a bereaved lover. Downtown by the female author Fumiko Hayashi is a beautifully written story of a gentle love between two paupers. Nightingale by Einosuke Itō, depicts country life through the daily events at the local police station with each visitor in this comic tale illustrating the workings of cause and effect on a small scale.

Most probably man had evolved in such a way that he could not see his own face. Maybe dragonflies and praying mantises could see their own faces. But then perhaps one’s own face was for others to see. Did it not resemble love? – The Moon on the Water, Yasunari Kawabata

(Credit: Vintage)

Hard-boiled Wonderland and the End of the World by Haruki Murakami and translated by Alfred Birnbaum

(Vintage, 2001)

No list would be complete without the inclusion of Murakami. No doubt he is the most widely read Japanese author outside Japan. Much like the film world’s Stanley Kubrick, or Akira Kurosawa, Murakami is a genre of his own.

Murakami often mentions Russian and French classics: Turgenev, Dostoevsky, Rudin and Stendhal to name a few. There are references, motifs and plots akin to Shakespearian tragedies. His fondness and high regard for such authors reflects how the same writers influenced the Japanese literary giants of late 19th-and-early 20th Century. It is not a coincidence that the nihilistic, psychoanalytical focus is similar. However, what makes Murakami unique is his ability to intertwine reality with the surreal, pulling in references to another universe of his own creation.

Every book lover has their favourite Murakami title. Hardboiled Wonderland and the End of the World is mine. It showcases his talent of incorporating different dimensions quite literally: here are two books proceeding at once, each chapter switching between stories. The storylines are separate yet there is a commonality. It begs the question of whether our dreams are more real than reality

I tried to picture my own head stripped of skin and flesh, brains removed and lined up on a shelf, only to have the old guy come around and give me a rap with stainless-steel fire tongs. Wonderful. What could he possibly learn from the sound of my skull? – Haruki Murakami

(Credit: Vintage)

The Housekeeper and the Professor by Yoko Ogawa, translated by Stephen Snyder

(Vintage, 2019)

Ogawa is an important contemporary writer who has won every major Japanese literary award including the Akutagawa and Tanizaki prizes. Her narrators, often female, offer a sympathetic explanation of sentiments and observe the story unwind from a distance – a subtle distance that women are kept at within Japanese society. And while the other books on this list are ostensibly set in Japan, this book is place-less, it transcends space and culture. It is, in many ways, the perfect book on which to end our exploration of Japanese literature.

The Housekeeper and the Professor is a story of love, in all its iterations. The love of mathematics and the beauty that lies in the wonder of numbers. The love of baseball, the sweat and tears. The love between a mother and son. The uninvited love between a wife and her husband’s brother. And the love between an unlikely pair: a professor with memory-loss and a fatherless boy.

As with all good books, the worlds created by the authors linger far beyond the final pages. While Japanese literature can be elusive, it can also guide us to a deeper understanding not just of Japanese life, but also of ourselves and of humanity.

Leave a comment